The narrow path to the new normal

Author: Bevan Graham, Economist at Salt Funds Management

The global economy enters 2026 at a delicate stage. On the one hand, the extraordinary turbulence of the early decade including pandemic disruptions, energy shocks, and policy volatility continue to fade into the background. However, evolving in its place is a still fragile “new normal” which encompasses a tougher global trading environment, lower trend growth, difficult fiscal challenges, inflation moving towards target (but in many cases not quite there), and rate-setting policymakers treading the fine line between economic stimulation and economic strangulation.

Structural growth challenges exposed

As growth gravitates towards new (lower) normal trend levels it will expose the underlying strengths and weaknesses of various economic models that have been masked for years.

The era of easy disinflation, cheap capital, and frictionless globalisation allowed many economies to grow without confronting hard structural choices. That period is now over.

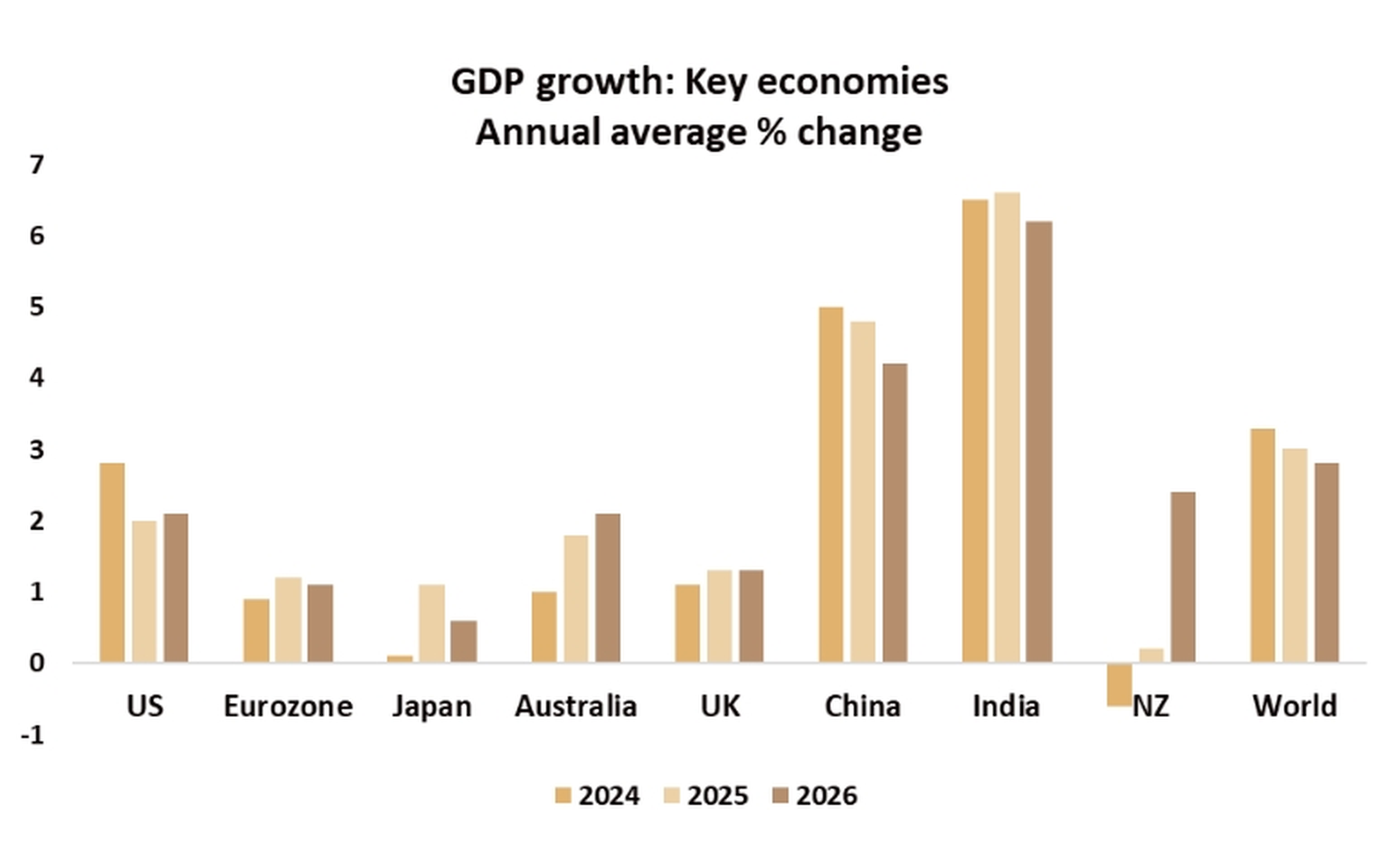

The United States enters 2026 as still the most dynamic developed world economy. Flexible labour markets, a strong culture of innovation, and a corporate sector that adapts quickly to technological change should see the US remain as a strong performer and contributor to global growth. But even the US is not immune to longer-term pressures. Higher borrowing costs, a shrinking labour supply from slowing immigration (one of Trump’s key policies), and a fiscal stance that cannot stay expansionary forever, make for a problematic combination of headwinds.

In Europe, the cracks are more visible. Weak productivity growth, rigid labour markets, and elevated energy costs continue to challenge competitiveness. For economies that rely heavily on trade into a fragmenting global system, growth looks fragile. Improvements in economic prospects are increasingly reliant on necessary domestic reforms. Japan faces similar demographic constraints, where a shrinking workforce risks keeping domestic demand soft, with an offset provided by labour-saving investment.

China’s structural challenges are the most pronounced. The transition from property-led expansion to a more balanced model is proving slow and uneven, weighing on confidence and leaving the economy vulnerable to deflationary forces and continued capital misallocation. Meanwhile, India and parts of Southeast Asia are establishing themselves as new engines of global growth - but their rise also reflects a shift in the geographic distribution of opportunity, not just cyclical momentum.

On balance, global growth in 2026 should reach around 2.8%, slightly softer than the estimated 3.0% in 2025. Should this transpire, it would mark the second consecutive year that global growth has come in below the long-run average of closer to 3.5%, a level that now seems something of a stretch target.

Fragmenting globalisation

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, increasing globalisation was a key driver of global growth and played a significant role in reducing inequality between countries. Markets used to view trade frictions as cyclical annoyances, or as episodic disruptions that would soon be resolved by economic pragmatism. But in 2026, geopolitical rivalry, national-security priorities, and industrial policy are on course to make trade fragmentation a structural, not a temporary, feature.

The shift can be seen in three clear trends. First, tariff and non-tariff barriers are expanding, with major economies turning to tradepolicy as an instrument of strategic competition. Second, supply chains arebeing redesigned for resilience rather than cost minimisation. Third, globaleconomic alliances are shifting, becoming more fluid and more contested ascountries balance economic needs with geopolitical alignment. ConsiderIndia’s oil-based partnership with global pariah Russia, as an example. Despitehuge US tariffs being placed on the former, and sanctions buffetingthe economy of the latter, both sides doubled down on theiralliance in 2025.

These forces increase the cost structure of the global economy and reduce the disinflationary tailwinds that markets once took for granted. They also introduce persistent policy unpredictability. Geopolitics now behaves like a permanent source of uncertainty and potential disruption. Hopefully 2026 sees less tariff noise with several trade deals signed, and a less fractious US-China relationship. The US mid-term elections in the second half of 2026 may dissuade Donald Trump from causing too much more global friction, as his attention pivots towards domestic themes. The strength of the US economy will be an important electoralbattleground.

Ultimately, the broader economic consequences of a more fragmented trading environment are yet to fully emerge.

The AI wave and the productivity promise

Against this challenging backdrop, the most potentially transformative force is the ongoing AI-driven investment cycle. For the firsttime in years, the global economy is staring at a technology that couldmeaningfully lift productivity, something most advancedeconomies have struggled with for decades.

However, unlike previous digital innovations,the AI revolution is capital intensive. It demands vast investment in datacentres, energy supply, cloud infrastructure, chips, specialised labour, andsecure supply chains. The “capital-light” era is over.

In 2026, the world sits at the intersection of immense promise but uncertain pay-off. If current trends continue, corporate investment should shift towards AI, perhaps even before the full productivity benefits materialise. This introduces asymmetry in the sense that the costs arrive early while the gains come later. Whenever expectations run ahead of uncertain realised economic benefits, the outlook is typically foggy. Only time will tell how long it takes forinvestor patience to run out (or not).

Still, if AI succeeds in raising productivity meaningfully,it could offset some of the structural drags from demographics, debt, andweaker globalisation.

Inflation down, but far from out

Inflation has slowed sharply as the pandemic-relateddisruptions to supply chains were resolved and central banks, albeit belatedly,tightened monetary conditions aggressively. However, the finalstep to target inflation has proven either temporary or elusive for manycentral banks. Service sector inflation, inparticular, has proved to be sticky.

Structural inflation drivers have shifted. Labour markets still exhibit firm wage growth in manyeconomies that are not offset by productivity gains. Supply chains areless efficient, and governments are using fiscal tools to pursue strategicaims, even as large structural deficits persist.

The result is a higher neutral rate than prevailed throughmost of the 2010s. As we enter 2026, central banks will therefore need totread carefully. Cutting (interest rates) too slowly risks chokingoff economic momentum, while cutting too aggressively risksreigniting inflation pressures.

Some countries should be able to lower interest rates a little further but cuts similar to those in 2025 areunlikely to be repeated.

Fiscal duress

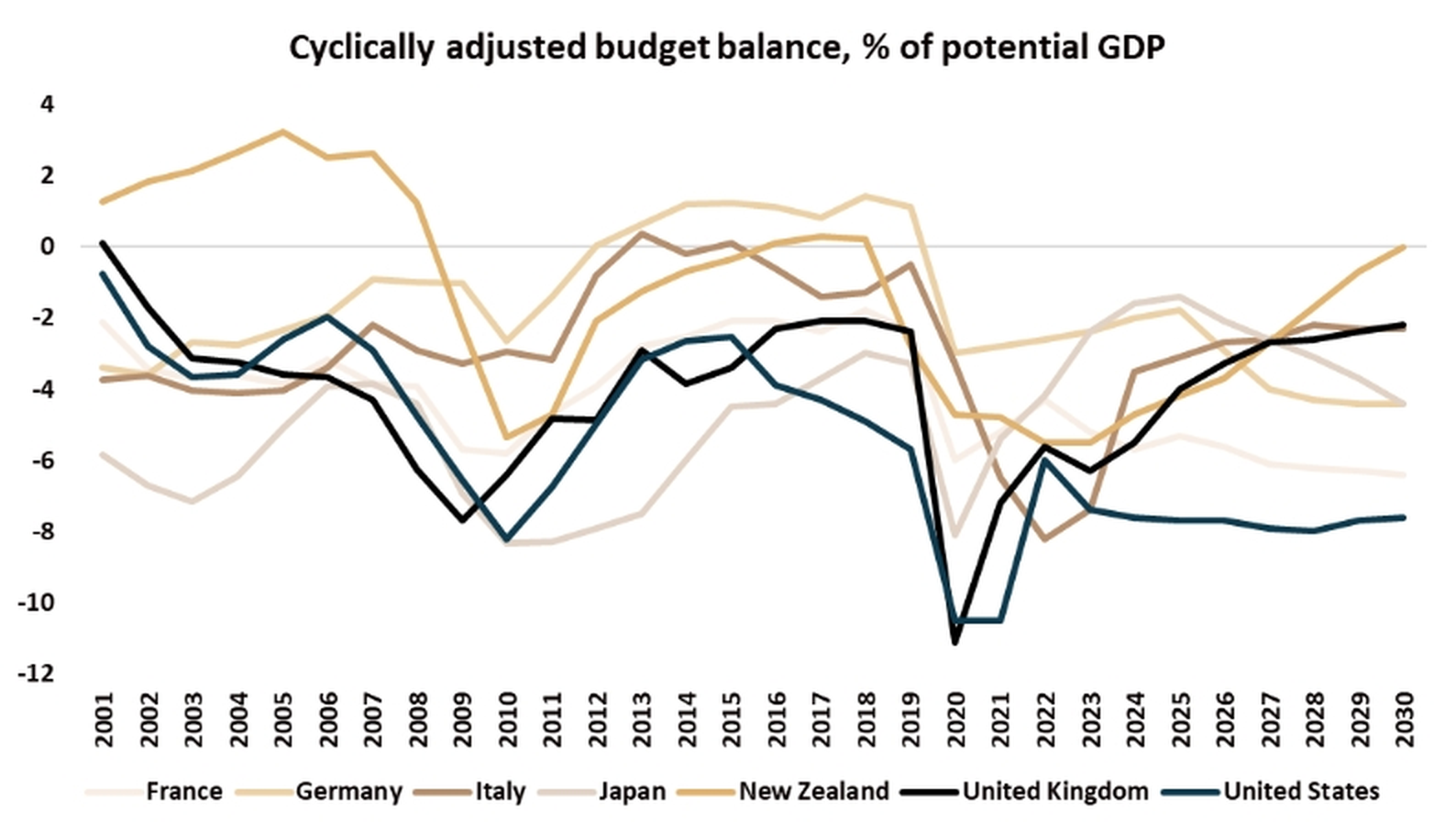

If monetary policy is shifting gears, fiscal policy enters 2026 under growing strain. Governments worldwide carry debt loads far higher than before the pandemic, and many now face rising interest costs, aging populations, and political constraints on consolidation.

For years, financial markets tolerated high debt on the assumption that low interest rates made it manageable. That assumption no longer holds. With real rates structurally higher, debt servicing consumes a growing share of national budgets. The resulting squeeze limits governments’ ability to invest in long-term priorities, from climate transition to healthcare to digital infrastructure.

At the same time, political incentives often lean towards short-term relief rather than long-term discipline. This tension between political promises and fiscal arithmetic will become increasingly visible in 2026, especially in economies with weaker institutional anchors or less credible fiscal frameworks.

The bottom-line

The global economy continues to navigate a path to the new normal. The challenges are immense, but there are also significant opportunities.

In 2026, investors will be hoping that AI starts to confirm the reality of its much-hyped capabilities. Until such point, the fear of uncertain returns will continue to stalk markets.

With regards to central banks. they will need to normalise their evolved monetary policies without destabilising economies. Meanwhile, governments, especially those with growing debtburdens, must reconcile political ambition with fiscalreality.

In summary, the global economy looks set for a relatively low period of growth. As ever, the onus is on investors to find the pockets of reward, whilst maintaining appropriate levels of diversification to help weather the pockets of volatility that will inevitably appear.

Photo credit: Gigi for Unsplash