New Zealand: Starting to fire

Written by Bevan Graham, Economist at Salt Funds Management

It has taken a while, but the New Zealand economy is finally starting to fire. The recovery was delayed by the absence of two traditional tailwinds of New Zealand economic growth: population growth as net migration slowed, and the wealth effect of rising residential property prices as house price inflation remained subdued. That left the recovery reliant on recently higher commodity prices and the resulting rise in the terms of trade, and lower interest rates that were always going to take time to impact on household disposable incomes given the high level of fixed rate mortgages.

The first half of 2025 was volatile from a GDP growth perspective. Growth of +0.9% quarter-on-quarter (q/q) in the first 3 months of the year was followed by a disappointing contraction of -0.9% in the second quarter1. While we don’t dispute the June quarter was weaker than the March data set, we think the magnitude of both the growth and, more importantly, the subsequent contraction were overstated.

As we entered the second half of the year, the data started to hint at better times ahead. Retail sales put in a ripper result in the September quarter, with sales volumes rising 1.9% in the three-month period. While we don’t expect this magnitude of growth to be maintained, it bodes well for a more sustained period of higher activity in 2026. Continued low population growth and only modest gains in house prices will keep the overall level of GDP growth constrained, despite lower interest rates continuing to feed through to thosehouseholds with a mortgage.

Against that backdrop, we see annual GDP growth in NewZealand of 2.4% in 2026, up from an estimated 0.3% in 2025.

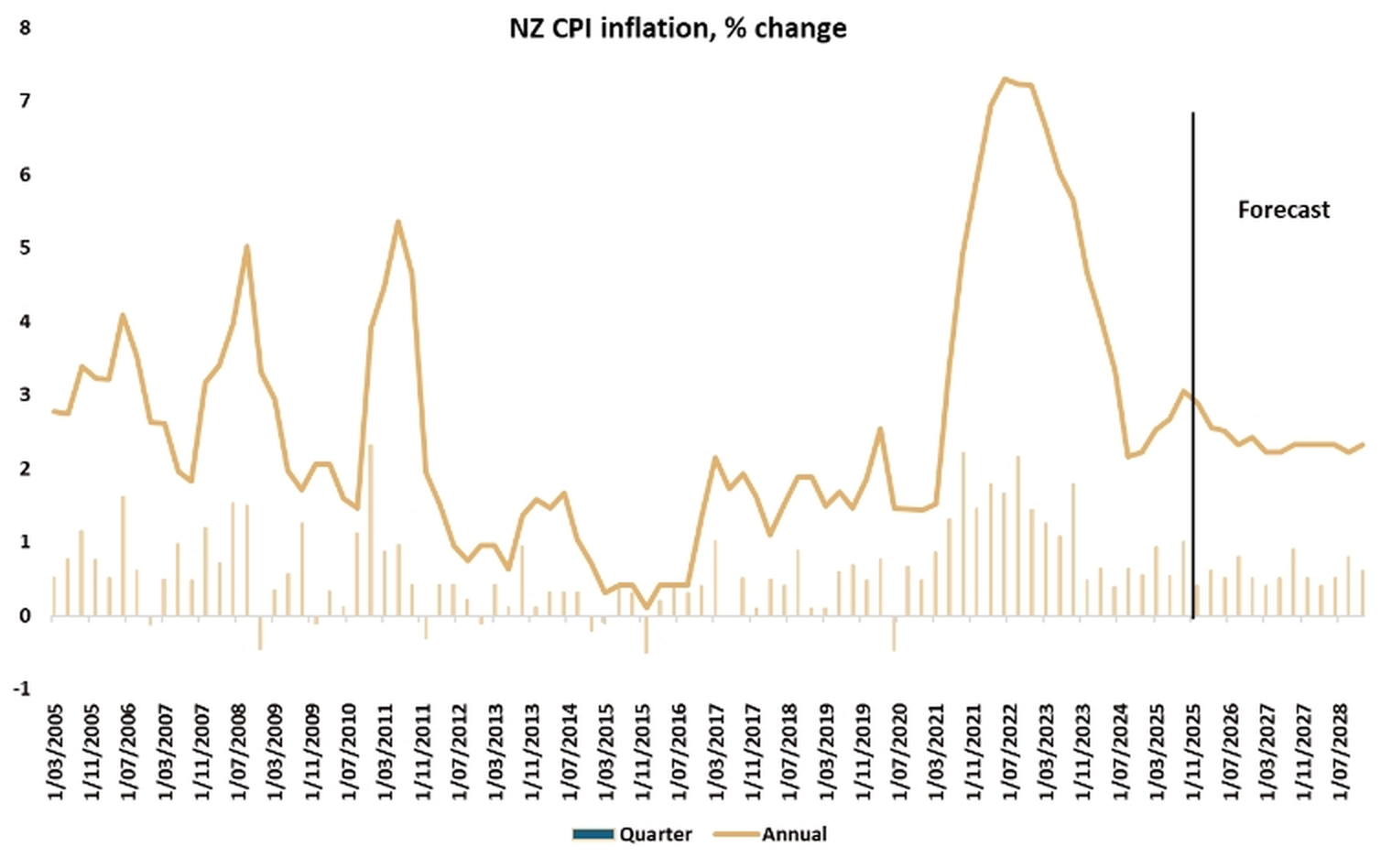

Headline inflation to fall back towards 2%

Headline inflation fell to 2.2% in the year to September 2024, but then headed up again as higher electricity, local authority rates, and food prices fed through into the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

The annual rate of CPI inflation reached 3.0% in the year to September2, the top of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s 1-3% target band. Based on current conditions, we expect the annual rate of inflation to head lower into 2026 as the impact of those past increases falls out of the annual calculation.

There are risks to the expected lower inflation. First, higher recorded inflation could feed through into higher household inflation expectations which would make getting actualinflation back to 2% more challenging. The second risk is that aftertwo years of tough trading conditions, firms may look to increase prices torestore profit margins.

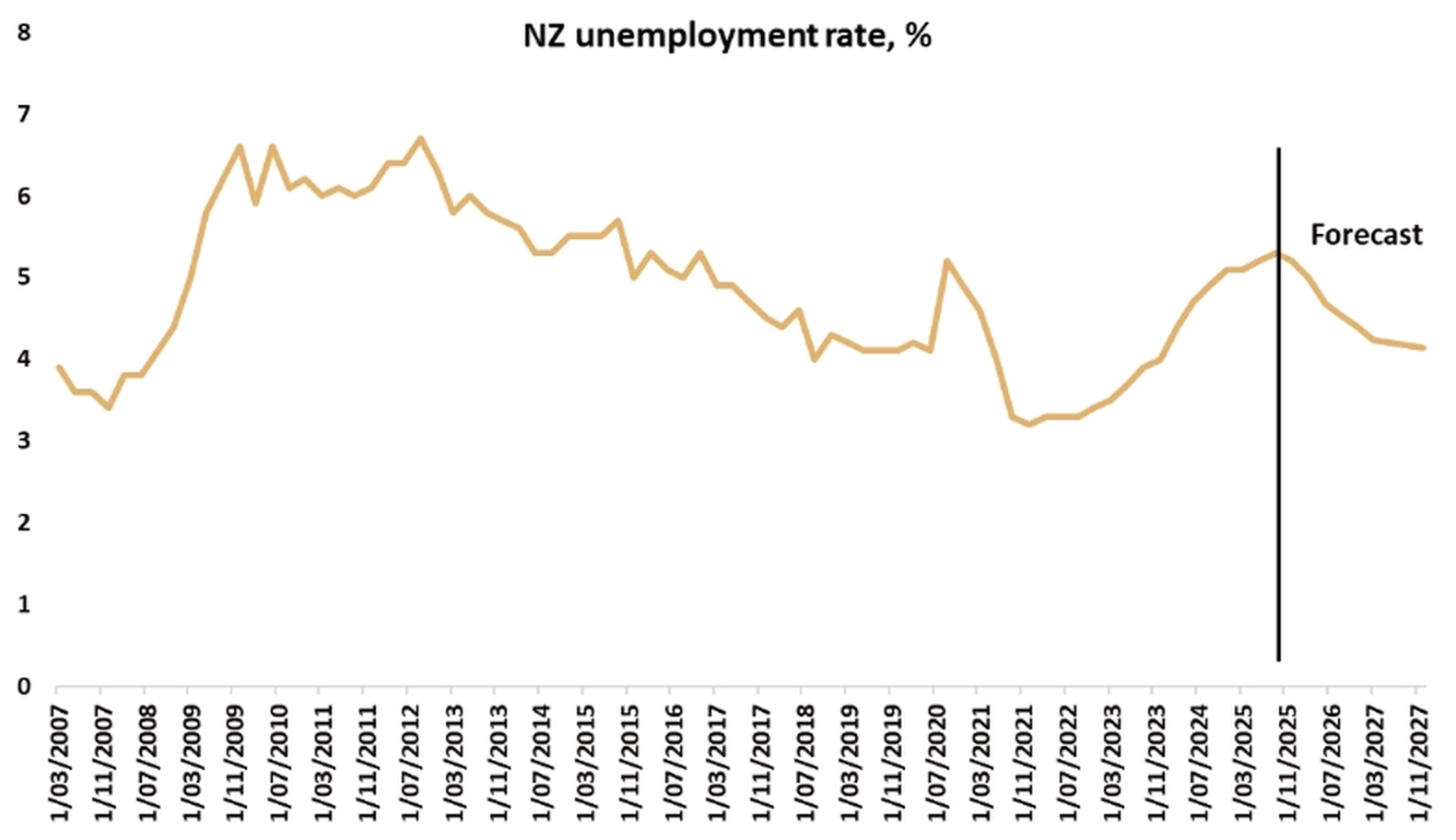

Employment will be slow to recover

However, with the unemployment rate at cyclical highs, wage pressure will remain subdued which will act to keep domestic inflation pressures in check. The unemployment rate increased to 5.3% in the September quarter, the highest level since the end of 20163. We expect this will be the peak in the cycle, but the recovery will be long and hard. Given our expectation of only modest growth in activitythrough 2026, the recovery in employment will also likely bemodest. Ad with an expected recovery in net migration adding to the supply of labour as the year progresses, we anticipate the unemployment rate will have only nudged down to around 4.5% by the end of 2026.

It is mostly due to the recent increase in the unemploymentrate, as well as the increased spare capacity in the economy that hasgenerated, that has allowed the RBNZ to lower interest rates.

At the peak in the interest rate cycle, the Official CashRate (OCR) reached 5.5%, but interest rate cuts that began in August 2024 haveseen the OCR reduced by a total 325 basis points to 2.25%4. Unless the nascent signs of economic recovery begin to falter, this will mark the lowfor interest rates this cycle.

Stable interest rates in 2026

Given the current monetary policy stance, 2026 should be ayear of relatively stable interest rates. However, as weget into the second half of the year, interest rate markets will probablybe starting to anticipate the first increase of the nextinterest rate cycle.

The issue for the RBNZ is that New Zealand has a relatively low potential growth rate. Potential growth is the rate of GDP growth an economy can sustain without generating abovetarget inflation. The RBNZ will therefore need to start raisinginterest rates before growth becomes so strong it risks the upside of theirinflation mandate.

In our view, that first increase is likely to come aroundthe start of 2027. If the upside inflation risks manifestthemselves, it could well be earlier.

Election year

Finally, 2026 is election year in NewZealand. There will be the usual wide range of issues for voters tocast their vote on and that will determine the shape of the nextParliament. From a financial market perspective, the electionis shaping up as a contest defined by growth, productivity, and fiscalcredibility.

Fiscal choices will be front and centre. Room for large-scale stimulus is limited by rising debt and higher interest costs yet demand for improved public services and stronger climate and resilience investment remains intense. Retirement incomes policy will also be a focus with a few political parties already announcing positions on KiwiSaver.

From a broader macro-economic perspective, the higher cost of living, higher neutral interest rates, and a constrained growth environment all add urgency to the debate about supply-side reforms.

The election will ultimately hinge on whom can credibly articulate a path to stronger, more inclusive growth without compromising long-term fiscal sustainability.

Photo credit: Israel Andrade for Unsplash